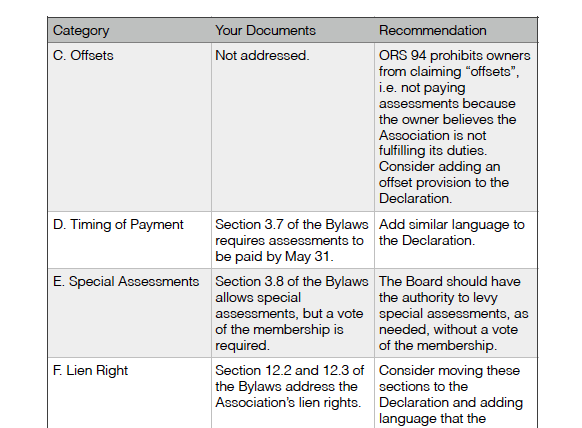

What is “Title”?

The term “title” has been defined as that which is the foundation of ownership, of either real or personal property, and that which constitutes a just cause of exclusive possession. It has also been defined as ownership, equitable or legal.

Title Companies

Before a title insurer or its agent can insure a transaction, it must operate a title plant in the county where the real property is located or purchase title insurance from a company that does. ORS 731.438(1). All title services by a title insurer must be provided within Oregon, and the information used to produce the services “must be maintained and must be capable of reproduction within the state at all times.” ORS 731.438(2).

A title plant can be jointly owned and maintained in “any county with a population of 500,000 or more, or any county with a population of 200,000 or more that is contiguous to a county with a population of 500,000 or more.” ORS 731.438(4).

Preliminary Title Report vs. Title Commitment

A PTR does not constitute title insurance. A PTR is also not a promise with respect to the state of the title of real property. It is simply an offer to issue title insurance in a particular form.

A title commitment is an agreement to issue a specified policy to a specified insured upon acquisition of the insurable interest, if accomplished within a limited time, and upon payment of the premium and charges.

Insurable Title

There is a difference between insurable title and marketable title. Title is insurable if the title company determines that, based on its examination of the public record, the company will deliver to the party to be insured a title insurance policy (i.e., a contract of indemnity) subject to the company’s usual printed exceptions and exclusions from coverage as well as subject to certain matters shown in the title report (e.g., a recorded easement).

Scope of Insurance

Title Vested

Any defect in or lien or encumbrance

Unmarketable Title

No Right of Access

Endorsements

Zoning - It provides assurance that the insured property is in a particular zoning designation and that certain specified uses are allowed in that designation. The endorsement does not insure, however, that any of the existing uses on the property are in compliance.

Access - The access endorsements provide additional assurances to the insured regarding access to the insured property, and can be used with owners’ and lenders’ policies. The endorsements specifically identify the physically opened street to which the insured property has access.

Environmental - The endorsements cover only loss sustained by reason of lack of priority of the lien of the insured mortgage over any environmental-protection lien recorded in the public records. The endorsements provide absolutely no protection to lenders regarding the numerous off-record issues raised by federal and state environmental laws.

Location of Improvements - the location-of-improvements endorsement assures that improvements having a specified street address or route or box number are located on the insured property.

Marketable Title

Marketable title is “title such as a prudent man, well advised as to the facts and their legal bearings, would be willing to accept.”

Abstract or Chain of Title

An abstract of title is also different from title insurance. An abstract is a summary of the chain of title to a particular parcel of property that shows how each owner acquired and disposed of the owner’s interest in the property. An abstract also discloses the nature and source of liens, encumbrances, and other matters appearing of public record in the chain of title.

Contents of a Title Report

Estate of Interest Covered

Fee Simple - The fee simple estate (also called “absolute estate” or “fee simple absolute”) is described as “full ownership.” A fee simple absolute is the most common estate in modern times; most people own their property in fee simple. The presumption is that a person conveys the fee estate unless the conveyance expressly states otherwise. The fee simple absolute is considered the greatest estate because it is of unlimited duration. The estate ends only by the sale of the property or the death of the holder without heirs. It is freely alienable, devisable, and inheritable.

Current Owner of Estate or Interest

Shows the current owner of record and how title is vested, i.e. single man, window, husband and wife.

Parcel of Land Involved/Legal Description

Rectangular or Governmental System - Under the Rectangular System of survey, the surveyors first established a reference point from which a line ran due north and south. This north-south line was designated the principal meridian. The principal meridian for Oregon is the “Willamette Meridian.” After establishing the principal meridian, the surveyors located a point on the principal meridian from which they ran a line due east and west. This east-west line was designated the baseline. In Multnomah County, the baseline for Oregon runs east-west along Stark Street east of the Willamette River and Burnside Street west of the Willamette River.

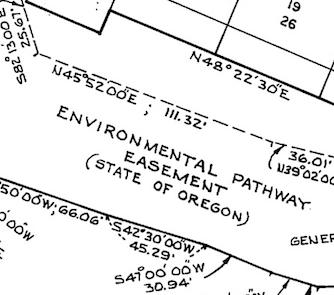

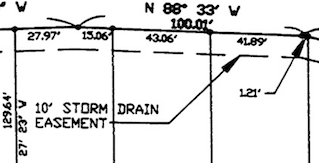

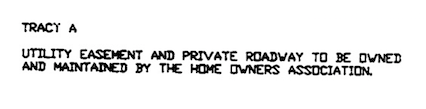

Subdivision Plats - Subdivisions (but not partitions) are named on the plat. In either case, the locations and descriptions of all monuments found or set must be recorded on the plat, and the courses and distances of all boundary lines must be shown. ORS 92.050(5). Each lot or parcel must be numbered consecutively, and the lengths and courses of all boundaries of each lot or parcel must be shown. ORS 92.050(4). When the subdivision or partition plat is completed and approved, and all required fees are paid, the plat may be recorded in the county records of the county where the described land is situated. ORS 92.050(1).

Metes & Bounds - A metes and bounds description typically contains an introduction defining the general location of the property by reference to the governmental survey, the place of beginning, and the body that describes the various courses of the property boundary by distance and bearing.

Liens

A lien is a claim or charge on property as security for payment of a debt or the fulfillment of an obligation.

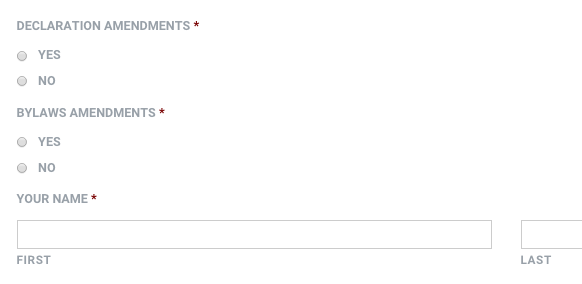

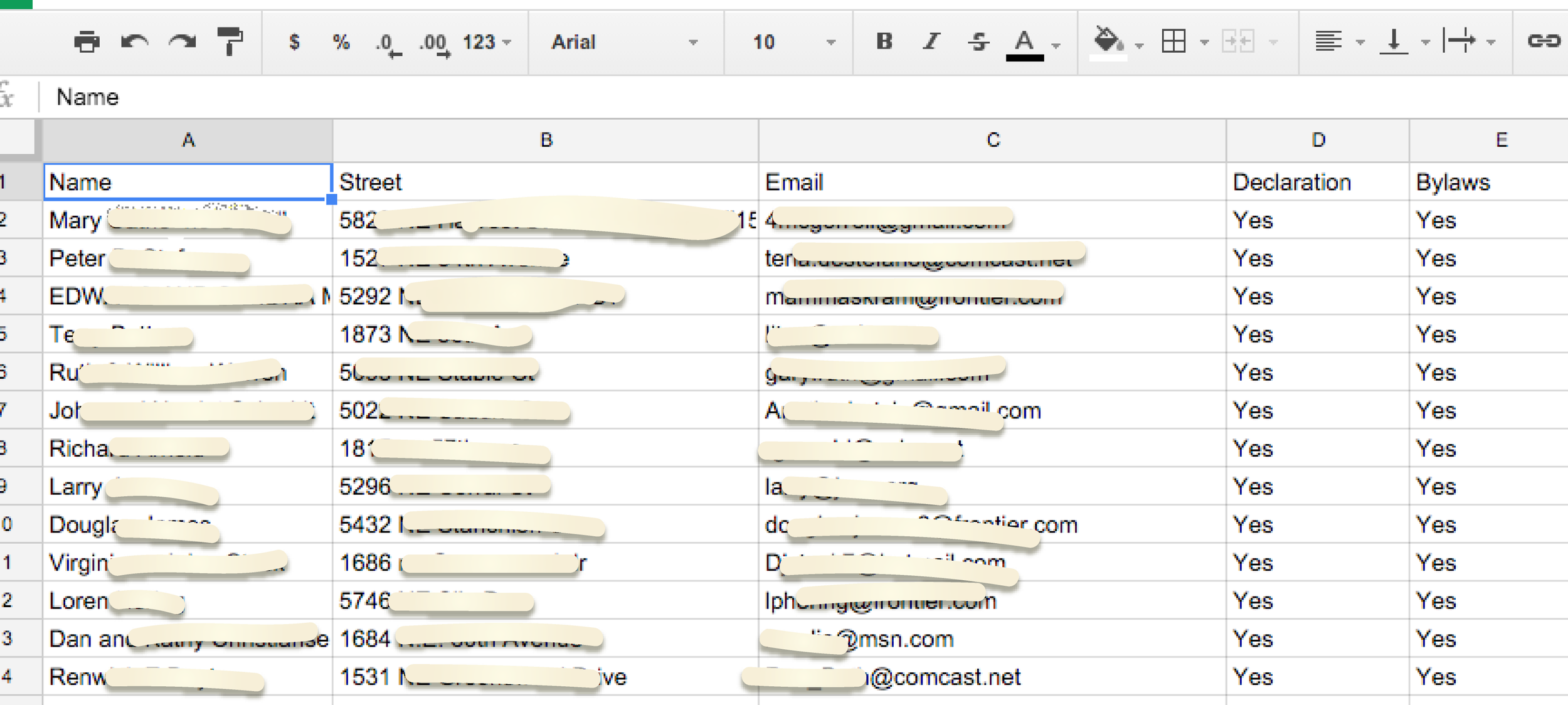

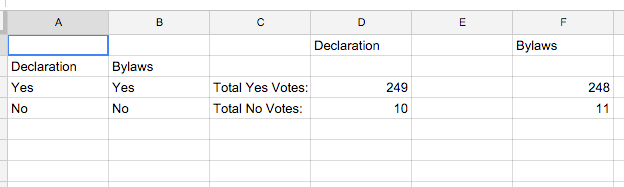

Covenants, Conditions and Restrictions

Covenants running with the land take different forms. When a single owner wishes to divide a parcel of land and create a scheme of contractual obligations binding on all future owners of the resulting parcels, the term declaration is an accurate description of what the owner does by recording a written statement of the covenants; hence the term declaration of covenants, conditions, and restrictions or CC&R declaration. Often, covenants are also included as a part of and literally on a recorded subdivision or partition plat.

Covenants and servitudes are important tools in private land use planning and regulation. Declarations of covenants, conditions, and restrictions (“CC&R declarations” or simply “CC&Rs”) for subdivisions often parallel public land use regulatory schemes and function as an overlay containing more restrictive requirements. In many instances, the CC&R declaration is coupled with an association, which is a quasi-municipal government for the project, providing services over and above the services provided by the local government.

Easements

An easement is a nonpossessory interest in the land of another that entitles the owner of the interest to a limited use or enjoyment of the other’s land and to protection from interference with this use. The interest, once created, may be irrevocable and generally is not subject to the will of the land owner.

Taxes

The first exception shown is a statement regarding the amount and status of the current year’s taxes (e.g., taxes now a lien, now due, or respective installment paid or unpaid).

Other Types of Title Insurance

Litigation Guarantee - The litigation guarantee is used by attorneys who are contemplating filing an action concerning the affected property, such as a quiet-title action, a partition action, or a suit to enforce an easement.

Foreclosure Guarantee - Judicial-foreclosure guarantees are issued to attorneys to indicate the status of the title and the parties to be named as defendants in a mortgage, trust deed, contract, or lien foreclosure suit. In addition to showing the status of title and the necessary defendants, a foreclosure guarantee shows all title exceptions that may or may not be pertinent to the contemplated foreclosure.