To learn more about amending your governing documents, check out our article: Amending Your Governing Documents

Amending Governing Documents

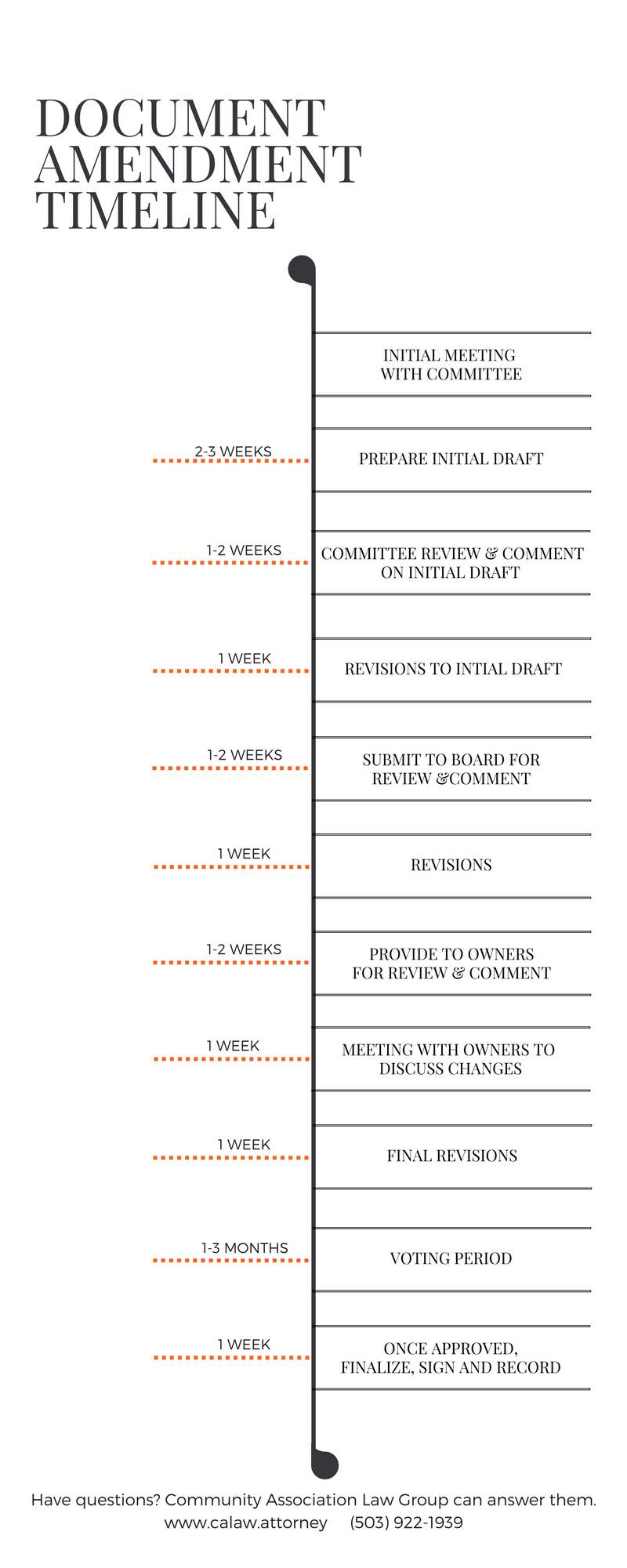

Amending your condominium or homeowners association governing documents is no easy chore. It can be a long and costly process, and even then, you may not receive enough votes to approve the amendments. The process of amending goes like this:

1. Identify the reasons for amendments 2. Determine any statutory requirements 3. Determine voting requirements 4. Decide on the method of voting 5. Solicit owner feedback on proposed amendments 6. Conduct the vote 7. Prepare the amendments for recording 8. Sign and notarize 9. Secure any governmental approvals 10. Record the amendments with the county recorder

Here are some things to consider before embarking on an amendment project:

Identify the Reasons for the Amendments

There are many reasons to amend governing documents. Common reasons include:

1. Legislative changes 2. Ambiguous provisions 3. Outdated provisions 4. Community demographic has changed 5. Removal of “declarant” language 6. Adding or removing restrictions

It’s critical that the reasons for each amendment are conveyed to the owners. After all, most amendments require owner approval. Making a convincing case to the ownership will result in higher voter turnout and more “yes” votes.

Find out What’s Required

Most CC&R amendments require a vote of between 65%-75% of the entire ownership. Bylaw amendments typically require a majority vote of the owners. However, sometimes state law will require different approval requirements. For example, in Oregon condominiums the approval of 75% of all owners is required for any amendment related to pet restrictions or the rental or leasing of units. (ORS 100.410(4)). In Washington, a homeowners association may amend its governing documents to remove discriminatory provisions by a majority vote of just the board of directors (RCW 64.38.028)

Method of Voting

Most associations will find it impossible to approve a governing document amendment at a physical meeting of the owners. For a CC&R amendment requiring 75% approval, the chances of that many owners attending a physical meeting in person or proxy is slim. The most common method is to conduct the vote by written ballot. Better yet, some communities may conduct the vote via online ballot. This often generates the most voter turn out. For an example of an online ballot, click here.

Finalize and Record

Once the required number of votes have been received, the amendment must be prepared for signature and recording. In some cases, approval by the state or a governmental authority must be received and reflected on the amendment. The amendment should contain references to the original documents which are subject to the amendments, and must be signed and notarized. The amendments do not become effective until recorded with the county recorders office.

Florida Amends Statute Governing Termination of Condominiums

This year the Florida legislature adopted Senate Bill 1520, governing the termination of condominium associations. You can review the changes here.

Oregon Condominium Conversions

Definitions

- “Declarant” means a person who records a declaration under ORS 100.100

- “Declaration” means the instrument described in ORS 100.100 by which the condominium is created and as modified by any amendment recorded in accordance with ORS 100.135 or supplemental declaration recorded in accordance with ORS 100.120.

- “General common elements,” unless otherwise provided in a declaration, means all portions of the condominium that are not part of a unit or a limited common element

- “Sale” includes every disposition or transfer of a condominium unit, or an interest or estate therein, by a developer, including the offering of the property as a prize or gift when a monetary charge or consideration for whatever purpose is required by the developer

Statutory Framework - The Oregon Condominium Act (ORS Chapter 100) governs:

-

- Formation

-

- Operation

-

- Sales

- Ownership Interests - Most condominiums consist of two types of real property: units and common elements. Each type is governed by substantially different rules regarding ownership, use, operation, and responsibility for maintenance, repair, and replacement.

- Units - The unit consists of the cubic air space created by the horizontal and vertical boundaries described in a condominium declaration. It is a separate parcel of real property capable of being platted, conveyed, and encumbered like any traditional parcel of real property.

- Common Elements - Generally, the balance of the property covered by a condominium plat not constituting units is called common elements. While units may be individually conveyed and encumbered, common elements, as their name suggests, are owned in common by all unit owners as tenants in common. Under the Oregon Condominium Act, common elements may not be conveyed, encumbered, or subjected to lien or attachment except under special circumstances. See ORS 100.440.

- General vs. Limited Common Elements - Common elements are further divided into two types: general common elements and limited common elements, which are distinguished from each other on the basis of right of use. A general common element is one that all unit owners are entitled to use on a nonexclusive, theoretically equal, basis, while use of a limited common element is restricted to less than all of the units (and typically to only one). See ORS 100.005(7), (16), (18). Some typical examples of limited common elements in residential condominium developments are decks, patios, assigned parking spaces, and courtyards. Limited common elements must be designated as such on the condominium plat, and their assignment to units and the description of use rights and limitations must be set forth in the condominium declaration and bylaws.

- Formation - To submit any property to the provisions of the Oregon Condominium Act (Condominium Act), the declarant must record a condominium declaration, bylaws, and plat in the office of the recorder of the county in which the property is located. ORS 100.100(1), ORS 100.115(1), ORS 100.410(1)

- Declaration - The required contents of any condominium declaration are set forth in ORS 100.105. In summary, for other than staged or flexible condominiums, the declaration must include a description of the property being submitted to unit ownership, a statement of the interest in the property, the name of the condominium project, the unit designation, a statement that each unit’s location is shown on the plat, a description of the boundaries and area of each unit, a description of the general common elements, and an allocation to each unit of an undivided interest in the common elements and the method used to establish that allocation. ORS 100.105(1).

- Bylaws - The Oregon Condominium Act (Condominium Act) requires the declarant to adopt on behalf of the association of unit owners the initial bylaws governing the administration of the condominium. ORS 100.410(1).

- Plat - A plat must be prepared and recorded simultaneously with the condominium declaration. ORS 100.115(1). The plat must comply with the requirements of ORS 92.050, ORS 92.060(1)–(2), ORS 92.080, and ORS 92.120 (requirements for surveying, preparing, filing, and recording plats). The plat must show the location of all buildings and public roads; show the designation, location, dimensions, and area of each unit, including the vertical and horizontal boundaries of each unit and the common elements to which each unit has access; identify and show, to the extent feasible, the location and dimensions of all limited common elements described in the declaration; and include a statement of a registered engineer, architect, or surveyor certifying that the plat fully and accurately depicts the boundaries of the units of the buildings and that construction of the units and buildings as depicted on the plat has been completed. ORS 100.115(1)(a)–(d).

Approvals

-

- Oregon Real Estate Agency - The Oregon Real Estate Agency carries out the provisions of the Condominium Act. See ORS 696.490(2) (appropriating funds for that purpose). The agency will review for substance and form both the original executed condominium declaration and bylaws, and copies of the condominium plat. The agency will also require the submission of a subdivision guaranty, a form of title insurance in favor of the agency, covering the property covered by the declaration.

- City or County - Depending on whether the property is located in a city or in an unincorporated county, the local government surveyor, tax collector, and tax assessor must review and approve the condominium declaration and plat. The city or county surveyor may be required to execute the plat.

Disclosure Statement

-

- General Description

- Sale Agreements

- Warranties

- Common Expenses, Assessment and Budget

- Operation and Management

- Declarant / Developer Rights

- Governing Documents

Reserves & Reserve Studies

-

- The Oregon Condominium Act requires all new condominiums to establish a reserve fund. The amount of reserves is based on a reserve study. The reserve study should be prepared by a qualified individual and identify all property and components with a useful life of 1-30 years. Reserves are only required for property or components which the Association is obligated to maintain, repair, or replace.

Conversions

- A conversion condominium is a condominium in which there is a building, improvement, or structure that was occupied before any sales activity and that is at least partly residential in nature. ORS 100.005(10). The legal requirements for nonconversion condominiums apply with equal force to conversion condominiums.

- Notice to Tenants - The declarant must give each tenant a notice of conversion at least 30 days before the declarant presents an offer to sell the unit to the tenant. ORS 100.305(3). The notice of conversion must include the following information:

-

-

- A statement that the declarant intends to create a conversion condominium;

-

-

-

- General information relating to the nature of condominium ownership;

-

-

-

- A statement that the notice does not constitute a notice to terminate the tenancy;

-

-

-

- A statement regarding whether the tenant’s unit will be substantially altered;

-

-

-

- A statement regarding whether the declarant intends to offer the unit for sale and, if so, a description of the tenant’s rights under ORS 100.310(1) to (3); a good-faith estimate of the approximate price range for which the unit will be offered for sale to the tenant; a good-faith estimate of the monthly operational, maintenance, and other common expenses or assessments attributable to the unit; a statement that financial assistance may be available from a local governing body, the Housing and Community Services Department, or a regional housing center; and a statement that the landlord may not terminate the tenancy without cause if the termination would take effect; and

-

-

-

- A statutory notice about restrictions on rent increases.

- The notice must be hand-delivered to the tenant’s dwelling unit or sent to the tenant at the unit’s address by certified mail, return receipt requested. ORS 100.305(1)(f).

-

Right of First Refusal - Before the declarant sells any unit to a third party in a conversion condominium without substantial renovation of the unit, the declarant must first offer to sell the unit to the tenant who occupies it. The terms of the offer are specified by statute. The offer terminates 60 days after the tenant receives it or upon the tenant’s earlier written rejection of the offer, and it must be accompanied by all of the applicable disclosure statements issued by the Real Estate Commissioner as required by the Oregon Condominium Act.

Timing - The Oregon Condominium Act provides that the notice of conversion must be given to a tenant at least 30 days before the declarant presents the right of first refusal to the tenant. ORS 100.305(3). In addition, the notice of conversion must be given at least 120 days before the conversion condominium declaration is recorded. ORS 100.305(1).

Regulation of Sales - Unlike condominium statutes in other states, the Oregon Condominium Act relates only to the sale (or resale) of units by developers and not to casual resales of single units by individual owners. The act defines a developer as a declarant or any person who purchases an interest in a condominium from a declarant, successor declarant, or subsequent developer for the primary purpose of resale. ORS 100.005(13).

Real Estate Contract Checklist

Real estate contracts can be complicated documents. Here's a checklist to make sure the necessary terms and conditions are covered in the contract.

- Date

- Seller Information

- Buyer Information

- Real Property Legal Description (not just address)

- Personal Property Included or Excluded

- Title to Convey

- Title Exceptions

- Purchase Price

- Down Payment

- Interest Rate

- Installment Periods

- Date of First and Last Installment

- Late Charge

- Prepayment Penalty

- Portion of Purchase Price to Allocate Toward Personal vs. Real Property

- Prior Encumbrances

- Insurance Requirements

- Zoning of Property

- Exhibits

- Possession Dates

- Default Provisions

Thinking Green This Tax Season

Tax season is among us— get green for going green this year. If you've purchased energy-efficient products or energy systems, you may be eligible for a $100 to $6,000 tax credit. Don't wait until next year, Oregon energy programs expire in December 2017.

For more information on Oregon's Residential Energy Tax Credit Program See Here.

2017 Legislative Update

Oregon and Washington law makers are in session. There are several proposed house and senate bills which impact condominium and homeowner associations. Here's a brief summary, along with links to review the language of the proposed legislation.

Oregon

SB 470 - Would prohibit CC&Rs, Bylaws, or Articles of Incorporation from prohibiting or restricting certified family child care homes. Read bill.

HB 2722 - In the event of a drought or water shortage, a condominium association may not require owners to irrigate landscaped areas. Read bill.

HB 3056 - Associations often file lawsuits against delinquent owners. If the association receives a court judgment, this bill clarifies that the judgment does not operate to release or extinguish the lien on the owner’s property. Read bill.

HB 3057 - This bill adds criteria for a board of directors to use when updating or reviewing the association’s reserve study. In addition, the proposed legislation changes the timeframe for financial reviews from 180 days to 300 days. Read bill.

HB 3094 - The current laws governing the restatement of governing documents is vague. This bill clarifies the meaning of “restatement” and establishes requirements for the board to follow when preparing and recording a restatement. Read bill.

Washington

SB 5134- This bill will give homeowners an objective timeframe of 45 days notice to be heard by the board of directors before the association may impose or collect charges for late payments of assessments. Read Bill.

SB 5250- Often times, it is very difficult for associations to obtain the required amount of votes to amend the bylaws due to non-participation. This law provides an alternative process for acquiring and counting votes to amend condominium bylaws. Read Bill.

Oregon Legislative Alert

Portland Landlord/Tenant Ordinance 188219 Also known as the “relocation assistance” ordinance, the temporary measure mandates that if a landlord raises rent on a tenant by more than 10% or evicts a tenant without cause, the tenant can demand the landlord to reimburse them for up to $4500 in moving costs. Actual amounts vary depending on size and cost of the unit, and the neighborhood. Small-scale landlords who manage only one rental unit are exempt. The short-term measure took effect immediately on February 2 and is retroactive for tenants who had received a 90-day no-cause eviction notice within the last 89 days. The law is meant to provide temporary relief for up to 8 months as the city remains under its official housing crisis.

Oregon currently has a statewide ban on rent control. Opponents to the new ordinance claim the ban violates this law. Supporters argue that it’s an effective policy in reducing forced displacement. On March 2, the Oregon House began hearings for House Bill 2004— an expanded version of the city ordinance that allows cities to impose rent control and prohibits no-cause evictions except in certain circumstances.

America's $275 Million Tilting Tower

Imagine if you spent $9 million on your luxury home only to discover afterwards it's sinking? Who's going to pay for the building's repair?

Why live near the water when you can live ON the water?

Thinking of buying a floating home?

Before buying, take a closer look at the perks and pitfalls of joining a floating home community.

Oregon Zoning Designations

Plat Maps and Surveys

The plat for your community is an important governing document. The plat is an aerial depiction of the lot boundaries, roadways, common areas, and easements. The filing of the plat and declaration is what creates the community. The plat contains a metes-and-bounds description of the development and the dimensions of each lot and unit. Plat maps can contain very important information. For example, it may show easements, utility line locations, and maintenance obligations--all of which may or may not be found in the CC&Rs or Declaration.

For planned communities, the plat also identifies the common areas. Sometimes, common areas are referred to as "Tracts". Here's an example of a plat depicting a common area, owned by the association:

Condominium and planned community plats are slightly different in the type of information which must be contained in the plat. For condominiums, plats must show the elevations of the units. For example:

If you do not have a copy of the plat for your community, you can get a copy from your county recorder or survey department. Here are the links to locate and download plat maps:

Understanding Governing Document Restatements

The process of amending governing documents is no easy task. Changes to the CC&Rs typically require between 66%-75% of the owners to approve. Bylaw amendments, on the other hand, are a little easier to modify, usually requiring a majority vote of the owners.

But suppose over the years your governing documents have been amended several times. Numerous amendments can make things complicated. When reading the CC&Rs or Bylaws, the reader must frequently refer to the amendments to confirm which sections have been modified.

“Restating” a governing document means combining the original document with all subsequent amendments. The association prepares a document incorporating all amendments and records a single “restated” version. Now, members can use and refer to a single document instead of an original and multiple separate amendments.

For example, let’s suppose your original Bylaws were adopted in 1995. In 1998 the association (via an amendment) increased the number of directors. Then, in 2000, the members voted to change the date of the annual meeting. Two years later, another amendment was adopted increasing the quorum requirement. Lastly, a recent amendment mandated that the board of directors carry liability insurance. Reading the Bylaws now requires the reader to review each of the amendments to ensure whichever section they are reading hasn’t been modified.

Oregon and Washington both provide procedures for restating. Washington, however, only addresses the process to restate the articles of incorporation. (RCW 24.03.183).

The procedure for Oregon planned communities and condominiums is the same. The board of directors adopts a resolution to prepare, codify, and record individual amendments. This does not require a vote of the owners. At the beginning of the restated document, the board must:

1. Include a statement that the board has adopted a resolution authorizing a restatement;

2. Not include any other changes which have not been properly adopted by the membership (except for scriveners’ error or to conform with format or style);

3. Include a certification by the president and secretary that the restated document includes all previously adopted amendments;

4. Cite to the document recording numbers of the previous amendments; and

5. Record the restatement in the county records where the community is located.

If your association has adopted multiple amendments over the years, talk with a qualified attorney and consider codifying and restating your documents.

Snow Removal in Community Associations

The Portland metro area and central Oregon are covered in snow and ice. As a result, dangerous conditions may exist in common area parking lots, sidewalks, or roadways. What is the community association’s obligation to clear or remove natural accumulations of snow and ice?

Some states have adopted the “Massachusetts Rule”. This rule states that property owners have no obligation to remove snow or ice from common areas under an association’s control. However, if the association aggravates the natural conditions, there may be liability. For example, suppose an association shovels snow from a walkway, but fails to put sand or salt on the surface. The walkway is now covered in a sheet of ice and has created an even more dangerous condition. In that case, there may be liability.

There are dozens of cases in different jurisdictions dealing with a property owner or association’s obligation for snow and ice conditions. For instance, in a number of cases in which an individual slipped and fell on ice or snow while walking on or across a parking lot, the courts, reasoning in general that a defendant was not liable for slip-and-fall accidents on natural accumulations of snow but could be liable for unnatural accumulations or aggravations of natural conditions, held that it was or could be proven that there was liability because the defendant plowed, sanded, or otherwise cleared the snow in a poor manner, or left icy or slushy ruts or tracks in which the plaintiff slipped.

Many court decisions have found that It is unfair to make a landowner or community association absolutely liable for every slip-and-fall accident on snow in a lot, especially as this would require the owner or association to spend the entire winter clearing the lot on pain of losing a liability suit. Moreover, it is equally unfair to require the lot owner or association to shoulder the expense of plowing and replowing the lot during the course of a continuous storm. In this vein, many jurisdictions have ruled that there is no liability for an accident that takes place while a storm is still going on or a reasonable time thereafter, to give the owner a chance to clear out the lot.

Here are the general rules of thumb for community associations:

1. If the Declaration or Bylaws requires the association to plow, shovel, or clear common areas, the association must do so. Many community associations, particularly in central Oregon, are obligated under the governing documents to provide snow removal. Use a licensed, insured, and bonded contractor to perform those services.

2. In the case where the association has no obligation for snow removal, there is a potential to create liability if the association engages in those activities.

3. If the association has common areas which are generally open to the public, there is typically an obligation to keep those areas clear of snow and ice, regardless of any requirements in the governing documents.

4. If the association has no obligation for snow removal, but decides to provide that service, it should hire a licensed, insured, and bonded contractor. The removal of snow or ice must result in a safer condition than leaving the natural accumulation on the common areas.

Disclaimer: By reading the information above, you do not become a client of the firm. The information provided above is based on general legal principles, and may not be applicable to you. If you have a legal issue or question, you should speak with an attorney.

Understanding Executive Session

Most condominium and homeowner associations in Washington and Oregon are subject to open board meeting requirements. The requirements are similar to the laws governing city councils and other governmental agencies. Conceptually, the policy behind open meeting requirements is that members of the community association are entitled to listen and witness the deliberation, discussion, and decision making of the board of directors.

Prior to any board of director meeting, notice must be given to all owners within the community. The notice must state the time and place of the meeting, and ideally, the meeting agenda. Owners are allowed to attend the board meeting, but because non-board members are not part of the “assembly”, owners do not have a right to vote or participate while the board is conducting its business.

There is an exception to the open meeting requirement: executive session. Executive sessions may be used so that the board can discuss private or sensitive topics behind closed doors. Keep in mind, no decisions are made in executive session—it’s only for discussion.

Here’s how the board should use executive session:

1. During a regularly noticed and scheduled board meeting, any member of the board may make a motion to adjourn to executive session.

2. The motion should indicate the general topic of discussion.

3. Once the motion passes, the board asks the audience to exit the meeting or the board moves to a different location.

4. The board then discussed the topic at issue.

5. Once the executive session is completed, the board moves back into the open meeting.

6. If there is an action item as a result of the executive session, a motion is made and a vote taken once back in the open meeting.

Remember, there are only certain topics which are appropriate for executive session. For Washington homeowner associations, those topics are:

1. Considering personnel matters;

2. Consulting with legal counsel or considering communications with legal counsel; and

3. Discussion of likely or pending litigation, matters involving possible violations of the governing documents of the association, and matters involving the possible liability of an owner to the association. (RCW 64.38.035)

For Oregon planned communities and condominium associations, the executive session topics are:

1. Consultation with legal counsel;

2. Personnel matters;

3. Negotiation of third party contracts; and

4. Discussion of delinquent assessments. (ORS 94.640, ORS 100.420)

Free Speech in Community Associations

Condominium and homeowner associations in Washington and Oregon often deal with free speech issues. Political signs are perhaps the most common issue. It is commonly misunderstood that owners have a right to display political signs. Generally, there are no free speech rights in community associations unless granted under the governing documents or state law. There are a few exceptions, though.

Some states, such as Maryland, have enacted statutes authorizing owners in community associations to display “candidate” signs. (Maryland Code Annotated, Section 11-111.2(c)). The Maryland statute specifically states that community association CC&Rs and rules may not prohibit the display of signs advocating for political candidates. Illinois has adopted a similar statute. (765 ILCS 605/18.4(h)).

Another exception is the Federal Flag Act. (18 USC 700, et. seq.). The Act prohibits community associations from barring the display of the American flag. Thus, if the association’s governing documents prohibit flags, that provision in the governing documents is void.

Free speech rights in community associations were given articulate treatment in a New Jersey Supreme Court case. (Committee for a Better Twin Rivers vs. Twin Rivers Homeowners’ Association, 192 NJ 344 (2007)). While the case is not binding in other jurisdictions, the reasoning and basis for the Court’s decision would likely be followed by most state courts. I’m attaching a copy of the decision to this letter.

I’ll explain the facts and discuss the outcome:

Twin Rivers is a planned community consisting of condominiums, townhouses, single family homes and commercial buildings. The community consists of nearly 10,000 residents. The Twin Rivers Homeowners’s Association is a nonprofit corporation created to oversee the affairs and operations of the community. Each owner, upon purchasing property in the community, becomes a members of the Association.

In early 2000, a group of owners formed the Committee for a Better Twin Rivers. The committee repeatedly placed signs throughout the community, and the Association promptly removed the signs each time. The Committee filed a lawsuit against the Association to invalidate its rules governing signs on the basis of free speech protection. The Association’s sign rules prohibited political signs on individual owner’s property and in the common areas of the community.

The case went through the trial court, the Court of Appeals, and ultimately to the New Jersey Supreme Court. In summary, the Court held that in order to enforce constitutional rights, there must be “state action”. This means that a governmental actor or entity must attempt to curtail an individuals free speech rights in order to trigger enforcement. Here, the court held that the Association’s enforcement of its sign rules did not constitute “state action” and that the owners’ expressional activities were not unreasonably restricted.

Condominium Review for Purchasers

Buying a condominium is a significant investment. Prior to purchasing, buyers receive numerous documents relating to the condition and operations of the condominium project. We will review those documents and provide an opinion on the overall health of the condominium. We will requested the following documents from the potential buyer:

- Declaration / CC&Rs

- Bylaws

- Rules and Regulations

- Meeting Minutes for the previous 3 years

- Reserve Study

- Maintenance Plan

- Articles of Incorporation

- Insurance Policy Declarations

After receiving the documents, we will provide an opinion on the following:

- Declaration or Bylaw provisions which are outdated or contrary to state law;

- An overview of the financial standing of the Association;

- Potential for construction defect issues;

- Any pending litigation;

- Restrictions on renting or leasing of units;

- Conflicts between rules/regulations and other governing documents;

- Adequacy of the Association's insurance coverage; and

- Whether the reserve account is properly funded.

Emergency Planning in Community Associations

Today, Portland and SW Washington are in a winter storm gridlock. If you have some free time over the next few days, take a moment to think about emergency preparedness and disaster recovery in your community association. Most importantly, make sure you have your insurance policy information and contact numbers handy at all times.

Here are some resources to review:

Here is a Red Cross family emergency planning chart: red-cross-disaster-family-plan

Here's a worksheet for community associations to review and fill out: disaster-plan-outline

Governing Document Review

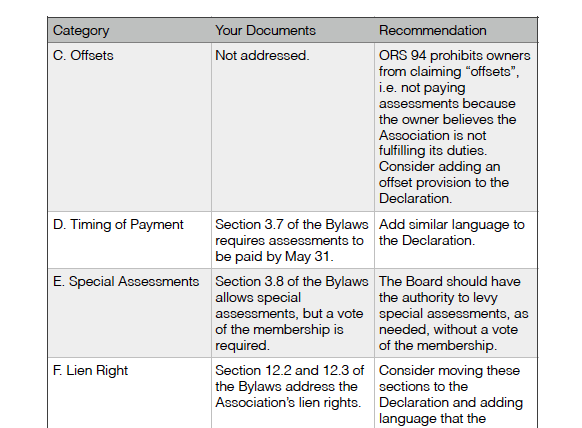

If your governing documents are old, drafted by the developer, or merely unintelligible, one of our lawyers will perform a thorough review of the association's Declaration/CC&Rs and Bylaws. The review lists each of the substantive provisions in your Declaration and Bylaws, as well as provisions which should be in the governing documents. Next to the provision is a recommendation or comment addressing whether the provision is out-dated, should be amended, or should be left as-is. Example:

For associations considering amending the governing documents, this is a great starting point to determine which sections need to be addressed.

Fill out the form below to get started:

[gravityform id="32" title="false" description="false"]

Short Term Rental Court Case Summaries

The following is a brief summary of cases from around the country. Each case deals with community associations and restrictions on renting. Watts v. Oak Shores Community Assn., 235 Cal. App. 4th 466 (2015)

A common interest development's homeowners association could adopt reasonable rules and impose fees on its members relating to short term rentals of condominium units because its covenants, conditions and restrictions gave its board of directors broad powers to adopt rules for the development, and nothing prohibited the board from adopting rules governing short-term rentals, including fees to help defray the costs such rentals imposed on all owners; That short-term renters cost the association more than long-term renters or permanent residents was not only supported by the evidence, but experience and common sense placed the matter beyond debate. Watts v. Oak Shores Community Assn., 235 Cal. App. 4th 466 (2015)

The Association has a rule stating that the minimum rental period is seven days. The Association's general manager testified that, based on his discussion with Board members, staff and code enforcement officers, as well as his review of gate and patrol logs, short-term renters cause more problems than owners or their guests. The problems include parking, lack of awareness of the rules, noise and use, and abuse of the facilities. Expert James Smith testified that, unlike guests, who are typically present with the owners, short-term renters are never present with the owner. Guests tend to be less destructive and less burdensome. Short-term renters require greater supervision and increase administrative expenses. A $325 fee is charged to all owners who rent their homes. A 2007 study calculated each rental cost the Association $898.59 per year.

Slaby v. Mt. River Estates Residential Ass'n, 100 So. 3d 569 (2012)

Property owners who engaged in a short-term rental of their cabin were not in violation of a restrictive covenant that provided for "single family residential purposes only," as the covenant did not require only owner occupancy, there was no required duration of occupancy indicated, and the rental was not a commercial use.

Yogman v. Parrott, 325 Ore. 358 (1997)

The ordinary meaning of "residential" does not resolve the issue between the parties. That is so because a "residence" can refer simply to a building used as a dwelling place, or it can refer to a place where one intends to live for a long time. In the former sense, defendants' use is "residential." The people who rent defendants' beach house use it as a temporary [***6] home, and their purpose is to engage in activities commonly associated with a dwelling place. For example, the record shows that they eat, sleep, bathe, and watch television there. On the other hand, if "residential" refers to an intention to live in a home for more than a temporary sojourn or transient visit, even defendants' own use of the property, as well as their rental use, is not "residential." Because of the different possible meanings of "residential," this portion of the restrictive covenant is ambiguous.

Seagate Condominium Association. v Duffy (1976, Fla App D4) 330 So 2d 484.

A provision of a condominium declaration which barred the leasing of any units except for limited periods of time under exceptional circumstances with the approval of the condominium association was held not to be unreasonable by the court.The court concluded that such a bar was not an unlimited or absolute restraint on alienation and was therefore to be judged in terms of its reasonableness. Noting that the problems of condominium living required a greater degree of control on the rights of individual unit owners than might be tolerated under traditional forms of ownership, the court concluded that the bar against leasing was neither an unlimited nor unreasonable restraint on alienation. The restriction was not unlimited inasmuch as the association could suspend its application in cases of hardship, and the court found it to be reasonable in view of the objective of inhibiting transiency and imparting a degree of continuity of residence.

Breene v Plaza Tower Asso. (1981, ND) 310 NW2d 730,

The court held that an amendment to a condominium declaration which prohibited the leasing of a condominium unit to a nonowner except in exceptional circumstances was invalid as applied to a condominium owner who purchased his unit prior to the adoption of the leasing restriction. Although the court noted that the condominium concept inherently required each owner to give up a certain degree of freedom he might otherwise enjoy in privately owned property, the court stated that such restrictions, to be enforceable, must be within the applicable statutory structure. Reasoning that the statutory provisions relating to condominiums contemplated that recording of the declaration, restrictions, and bylaws would place prospective purchasers and owners on notice as to the restrictions affecting their interest in the property, the court concluded that as a prerequisite to enforceability, the restriction must be recorded prior to the conveyance of any condominium unit. Consequently the leasing restriction adopted after the purchase of the condominium unit was not enforceable as an equitable servitude, the court said, except through the purchaser's acquiescence.

Re 560 Ocean Club, L.P. (1991, BC DC NJ) 133 BR 310.

Condominium association had no authority to restrict leasing of condominium units to certain minimum periods of time during summer months and during other times where restrictions on leasing, to be valid, had to be designated in recorded master lease and could not be inconsistent with state's condominium statute, and in instant case there was no specific reference in master lease to opportunity of association to restrict or limit duration of leases.

Woodside Village Condominium Ass'n, Inc. v. Jahren, 806 So. 2d 452 (Fla. 2002).

Condominium owners were bound by amendment to declaration that restricted leasing a condominium to nine months in a 12-month period, where owners were on notice when they purchased their units that the leasing provisions in the declaration could be changed byamendment, amendment was properly enacted under the amendment provisions of the declaration, and leasing restrictions did not violate any public policy or owners' constitutional rights.

Mullin v. Silvercreek Condominium Owner's Ass'n, Inc., 195 S.W.3d 484 (Mo. Ct. App. S.D. 2006).

Section of the condominium declaration stating that no business, trade, occupation or profession of any kind shall be conducted, maintained or permitted on any part of the property was not intended to restrict the right of any condominium unit owner to rent or lease his condominium unit from time to time.