Attorney Bruce Lepore joined the firm full-time on May 1. Prior to law school, Bruce owned and operated a recruiting company in Tokyo. Shortly after selling his company, Bruce moved to Central Oregon where he managed condominium and homeowner associations. Bruce graduated in the top 5 of his law school class and will focus on community association law and real estate disputes. He will join the firm as an equity partner. We are excited to have Bruce as part of the team.

Washington Uniform Common Interest Ownership Act (UCIOA)

In February of 2018, the State of Washington enacted a version of the Uniform Common Interest Ownership Act (UCIOA), which became effective on July 1, 2018. That act was intended to replace the previously enacted Washington Condominium Act and Washington Homeowner’s Association Act.

Under UCIOA, “common interest community” is defined to include condominiums and homeowner’s associations. It applies in full to any condos or HOAs created after July 1, 2018 (with an exemption for very small communities, defined as 12 or less units and less than $300 per year in assessments). Two subsections of the Act apply to condos and HOAs created prior to July 1, 2018. Board members should be aware of each of these two subsections.

RCW 64.90.525: Budgets—Assessments—Special assessments

Subsection 90.525 governs the procedure for adopting annual budgets, annual assessments, and special assessments. This provision applies to all residential common interest communities (exempting smaller communities as noted above), and overrides any contrary provisions in the governing documents or previous statutes. Because setting budgets and assessing the owners is a primary function of the Board, it behooves Board members to understand these procedures in detail. The text of this provision is relatively straightforward, so I’ve simply included it here for reference:

(1) (a) Within thirty days after adoption of any proposed budget for the common interest community, the board must provide a copy of the budget to all the unit owners and set a date for a meeting of the unit owners to consider ratification of the budget not less than fourteen nor more than fifty days after providing the budget. Unless at that meeting the unit owners of units to which a majority of the votes in the association are allocated or any larger percentage specified in the declaration reject the budget, the budget and the assessments against the units included in the budget are ratified, whether or not a quorum is present.

(b) If the proposed budget is rejected or the required notice is not given, the periodic budget last ratified by the unit owners continues until the unit owners ratify a subsequent budget proposed by the board.

(2) The budget must include:

(a) The projected income to the association by category;

(b) The projected common expenses and those specially allocated expenses that are subject to being budgeted, both by category;

(c) The amount of the assessments per unit and the date the assessments are due;

(d) The current amount of regular assessments budgeted for contribution to the reserve account;

(e) A statement of whether the association has a reserve study that meets the requirements of RCW 64.90.550 and, if so, the extent to which the budget meets or deviates from the recommendations of that reserve study; and

(f) The current deficiency or surplus in reserve funding expressed on a per unit basis.

(3) The board, at any time, may propose a special assessment. The assessment is effective only if the board follows the procedures for ratification of a budget described in subsection (1) of this section and the unit owners do not reject the proposed assessment. The board may provide that the special assessment may be due and payable in installments over any period it determines and may provide a discount for early payment.

RCW 64.90.095: Election of Preexisting Common Interest Communities

Subsection 90.095 also applies to all common interest communities, and provides a procedure by which communities created before July 1, 2018 may “opt in” to UCIOA. Under this subsection, the process of opting in is considered an amendment to the governing documents, but the voting threshold is reduced from the usual threshold required for amendment. This reduced threshold overrides any conflicting provisions in previous statutes or the governing documents themselves.

In short, the legislature adopted a mechanism that makes it relatively easy for communities to operate under UCIOA instead of the previously enacted Washington Condominium Act or Washington Homeowner’s Association Act. But, before explaining the procedure for opting in, I’ll first discuss some of the benefits of UCIOA over previous statutory schemes.

There are a number of benefits to opting in to UCIOA, particularly for pre-existing homeowner's associations. The previously enacted Homeowners’ Association Act (RCW 64.38) is relatively sparse and, frankly, inadequate. UCIOA, by contrast, is fairly robust and comprehensive. To see the difference, simply compare side by side the provisions governing the powers and duties of a homeowners’ association (RCW 64.38.020 vs. RCW 64.90.405). The new law adds a few useful powers that were previously absent, such as the power to provide for indemnification of directors and officers or the power to suspend rights and privileges of delinquent owners. The new law also places some important limits on board authority to convey common property or borrow money. It also clarifies the circumstances under which a board has an affirmative duty to enforce covenants, and when the board may decline to do so (which is a topic for an upcoming blog post).

In addition to being generally more robust and comprehensive, UCIOA has the benefit of applying equally to HOAs and condominiums. This makes it much simpler to understand the governing law (particularly for the association’s lawyers). UCIOA also provides for the option of conducting votes of the membership in lieu of a meeting (RCW 64.90.455). This is a particularly useful provision for associations where it is difficult to get the required number of owners to attend a meeting. In addition, UCIOA provided associations a right to enter the privately owned lots in order to maintain common property or inspect for violations of the governing documents.

The procedure for opting in to the UCIOA is rather simple, despite the convoluted wording of RCW 64.90.095. Under subsection (3), regardless of what amendment provisions are included in an Association’s governing documents, the following procedure may be used to opt in to UCIOA:

(1) The amendment to opt in to UCIOA may be proposed to the Association in one of two ways. Either the Board may propose the amendment or owners holding 20% of the total votes in the Association may bring a petition proposing the amendment.

(2) The Board then prepares a proposed amendment document, along with a notice of a “town hall” meeting to be called to discuss the amendment. The notice of the town hall meeting and the proposed amendment must be delivered to all owners at least 30 days prior to the meeting. The statute does not include any quorum requirement for this meeting.

(3) Once the meeting has been held, the Board prepares a ballot and notice of a vote. The ballot and notice must be delivered to each owner.

(4) At least 30% of the total voting power must participate in the vote, and 67% of those participating must vote to approve the amendment.

In essence, this means that only 21% of the total voting power must actually approve the opt in amendment for it to be valid. This is a relatively low threshold and one that can probably be obtained even in the most apathetic or disinterested communities. Although the process for opting in to UCIOA does involve some initial effort and expense, as noted above, this new law should make things easier for common interest communities in the long run.

Attorney Kevin Harker files lawsuit to enforce CC&RS

Read the article here in the Bend Bulletin.

Forming an Oregon HOA

Many (mostly older) Oregon subdivisions have recorded CC&Rs, but no homeowners association to enforce or administer those CC&Rs. The Oregon Planned Community Act, ORS Chapter 94, lays out a procedure to form a homeowners association in certain types of subdivisions. The process is described in ORS 94.574. Here's a summary:

The owners call for an organizational meeting to decide whether or not to create an association.

Notice of the meeting must be sent to all owners.

The notice must indicate who initiated the meeting, and a general overview of the purpose of the meeting. The notice may also include a statement that the owners will be asked to elect a board of directors and adopt Bylaws.

A majority of the owners must vote to approve the formation of the association.

Each lot in the subdivision is entitled to one vote. So, if there are 80 lots in the subdivision, at least 41 lots must vote to approve the creation of a homeowners association.

If enough votes are received, the owners should immediately vote to elect a board of directors, adopt Bylaws, and file Articles of Incorporation.

Generally, Oregon HOAs incorporate as nonprofit corporations.

Please contact us if you have any questions about the process to form an association!

How Long Do Oregon HOA Liens Last?

Homeowner associations in Oregon are governed by the Planned Community Act, ORS Chapter 94. Under that statute, homeowner associations have an “automatic” lien on any lot that is delinquent on assessments or dues. The automatic lien exists without filing or recording a traditional paper lien in the county records.

That said, in the event that the HOA decides to foreclose on its lien, then a traditional lien must be filed and recorded.

But how long does the HOA have to foreclose on its lien or file a suit against the delinquent owner? Under ORS 94.709, the HOA’s lien is valid for six years. This is consistent with the statute of limitations for breach of covenant or breach of contract, which is six years: ORS 12.080(1): “An action on certain contracts or liabilities must be commenced within six years.”

In short, Oregon HOAs have six years to attempt to collect delinquent assessments. This applies to collecting the assessment through foreclosure or through a lawsuit against the individual owner of the property. Once a delinquent assessment is more than six years old, the association will be prohibited from collecting the delinquent assessment under the statute of limitations

Oregon Landlords and Senate Bill 608

Oregon Senate Bill 608 will likely become law this session. The legislation prohibits landlords from increasing rent by more than 7% (plus a calculation based on the CPI) on an annual basis.

In addition, SB 608 prohibits a landlord from evicting a tenant after the first year unless: 1) the eviction is for cause or 2) the landlord has a “qualifying” reason. The qualifying reasons include:

1. The landlord intends to demolish the living unit;

2. The premises is unsafe or unfit for occupancy;

3. Landlord intends for an immediate family member to live in the unit; or

4. The landlord has accepted an offer to purchase.

If the landlord has a qualifying reason, the landlord must provide notice to the tenant and pay the tenant an amount equal to one months rent. The requirement to pay the tenant one months rent does not apply if the landlord owns four or less rental units.

Here’s a news article on the legislation.

You can review the bill here.

2019 OREF Form Changes

Many of the standard Oregon Real Estate Forms have been updated for 2019. Click here: for presentation slides on the 2019 changes. One significant change involves FIRPTA (Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act). From now on, sellers of residential property must prepare and submit a FIRPTA regardless of whether the Act applies. Thus, even if FIRPTA does not apply, the seller must prepare and submit a form indicating that the Act is not applicable.

OREF prepared the following practice tip:

“BEST PRACTICE - The Seller should fill out the form and send it directly to the escrow agent so that the social security number is not made available to the broker or staff. However, the Buyer’s agent, in particular, should confirm that the escrow agent has this form. The certification (or payment) is the only protection that the buyer has that they are exempt from or complied with the requirements of the Act. It appears that all escrow companies are willing to act as the Qualified Substitute in the event there is a foreign seller; however, some may limit the personnel who can act in this capacity so it will be necessary to check as to the company’s position. In this instance the Qualified Substitute (escrow agent) will collect and disburse the appropriate amount to the IRS. If you are the Seller’s broker and they are a foreign person, be sure that they have a Taxpayer Identification Number (“TIN”) as the Qualified Substitute (escrow agent) can not disburse funds within the 20 day time limit without this number. It can take weeks to secure this number from the IRS. It is recognized that the number of Foreign Sellers who will require withholding is a relatively small percentage in most areas; however, the liability of 10-15 % of the gross sales price is significant and should be eliminated. The option of deciding who might be a “foreign seller” is fraught with potential claims of discrimination or outright mistake; herefore, the only safe option is to require this certification from every seller.”

Using Proxies in Community Associations

Oregon and Washington law authorize the use of proxies unless prohibited by the governing documents. (RCW 24.03.085, ORS 65.231) Many condominium and homeowner associations find it impossible to achieve quorum at annual meetings without the use of proxies.

A proxy is a power of attorney between the “proxy giver” and the “proxy holder”. The proxy holder attends the ownership meeting and can act on behalf of the proxy giver, including making motions, voting, and engaging in debate.

When to Use Proxies

Proxies are typically exclusive to membership meetings, and in most cases should not be used for board meetings. Board members are elected specifically because owners trust the board member’s judgment, expertise, or knowledge. If a board member cedes their responsibilities to another individual, then they are not fulfilling their fiduciary duties. Oregon explicitly prohibits the use of proxies in board meetings. (ORS 100.419 & 94.641)

Types of Proxies

There are many types of proxies:

1. General proxies;

2. Directed proxies;

3. Proxies for the purpose of establishing quorum; and

4. Combinations of general and directed proxies.

General proxies are ideal unless circumstances require otherwise.

The Proxy Holder

Unless prohibited by the governing documents, the proxy holder may be any individual, including individuals who may not even live in the same community. For example, I could give my proxy to my grandmother who lives in another town. What’s important is that I give my proxy to someone I trust, and who will exercise good judgment.

Proxies and Voting

Keep in mind that giving a proxy to the proxy holder does not cast a vote. It merely authorizes the proxy holder to attend the meeting and then cast votes on behalf of the proxy giver. Proxies are not absentee ballots, and there is no such thing as a “proxy ballot”.

If the proxy giver wants the proxy holder to vote a certain way, then a “directed” proxy may be used. But there are downsides to directed proxies. Suppose I give my neighbor a directed proxy which instructs my neighbor to vote for Jill for the board. However, as the meeting begins Jill decides not to run for the board, and Jane steps into Jill’s place. Now, my directed proxy is useless (not quite useless, it still counts toward the quorum requirement).

Proxy Requirements

A proxy should contain the following information:

1. Name of association

2. Name of proxy giver

3. Proxy giver’s unit, lot or address

4. Name of proxy holder

5. Date when proxy giver signs

6. Expiration date

7. Signature

Click here for a sample proxy: Sample Proxy

Creating an HOA in Oregon

Creating a Homeowners Association in Oregon

Many older subdivisions have recorded CC&Rs but no homeowners association to govern the community. Who enforces the provisions of the CC&Rs? Who maintains the common areas? Who ensures compliance with the architectural requirements? As a practical matter, it often makes sense to have an HOA handle these issues, rather than an individual owner or group of owners.

The Oregon Planned Community Act (ORS Chapter 94) contains a process for owners to use to form an HOA. The procedure applies to pre-2002 communities with shared maintenance responsibilities (private roads, perimeter fence, entrance monument) and with CC&Rs that require owners to pay assessments.

The process is started when at least 10% of the lot owners initiate the process. Once that happens, here are the following steps:

Notice of an organizational meeting is sent to all lot owners in the community.

The notice must include the names of the individuals initiating the process, a statement that the purpose of the meeting is to form an HOA, and a copy of the proposed articles of incorporation.

In addition, the notice must state the required number of votes necessary to form the HOA. If the existing CC&Rs are silent, then at least a majority of the lot owners must vote to create the HOA.

Lastly, the notice must state that the owners will vote to elect a board of directors to govern the new HOA.

At the organizational meeting, a new board of directors is elected. The new board is then required to file the articles of incorporation and record any required documents in the county recording office.

Assuming the owners vote to form the HOA, all of the organizational expenses are a common expense shared by all owners. Now, this is a simplified version of the process. The statute governing the process (ORS 94.574) is a bit more complex, and you should consult a qualified attorney before embarking on the formation of a homeowners association.

But what if the subdivision has recorded CC&Rs but no shared maintenance obligations or payment of dues? In that case, the owners must amend the CC&Rs to form an HOA. The CC&R amendment would add provisions creating the HOA and authorizing the election of a board of directors. The required vote may be high. Some CC&Rs required the approval of at least 90% of all owners. In that case, it’s critical that owners understand the benefit and value of forming an HOA.

Once the amendment is approved and recorded, the owners should incorporate as a nonprofit and file articles of incorporation with the Oregon Secretary of State. In addition, the owners should adopt bylaws. The bylaws are the operational guidelines for the new HOA and the board of directors, and should be recorded in the county recording office.

The process to form an HOA can be complicated, and as always, you are encouraged to seek competent legal advice.

Importance of Real Estate Disclosures

This article illustrates the importance of seller disclosures in residential real estate transactions. Read the article here.

Withholding Assessments Won't Work

Sometimes community residents become dissatisfied with the association for some reason. In this case, let’s use maintaining the parking lot as an example. Mr. Homeowner is unhappy because several small potholes have appeared in the parking lot, and the association hasn’t repaired them. He called the manager who said that all potholes will be repaired in the spring. “It’s much easier and cheaper to fix them now, while they’re small,” Mr. Homeowner states. The manager explains the association’s maintenance schedule and states that parking lot repairs are scheduled, and budgeted, for spring.

Mr. Homeowner wants the potholes fixed now, so he decides to withhold his assessment payment until the potholes are filled. Sorry Mr. Homeowner, withholding assessments will not get the potholes filled. Here’s why:

You signed a contract with the association called the Declaration, or CC&Rs, in which you agreed to pay assessments. Period. There are no Unless Clauses in the Declaration—“I agree to pay assessments, unless . . .”

Yes, the association has an obligation to maintain the common areas. Since the repairs are on the maintenance schedule and in the budget, the association is fulfilling that obligation.

Filling every pothole as it appears throughout the winter isn’t economical. Agreed, it’s less expensive to fill a small pothole. However, it’s far less expensive to have only one visit from the asphalt company to repair all potholes—even the big ones.

Unfortunately, Mr. Homeowner, instead of getting the potholes filled immediately, you get a lien filed against your home for failing to pay your assessments.

But, let’s say the potholes get especially large before the end of winter and Mr. Homeowner fears they’re dangerous. He’s believes the potholes may cause damage to his car or he injure himself. He should call the manager and explain the situation. The association will make emergency repairs to protect owners and avoid liability.

If the association still fails to repair what Mr. Homeowner believes is a hazard, he has the right to pursue other legal channels to require the association to perform its duties. But, withholding assessments isn’t one of them.

We're Having What Kind of Meeting?

We're having what kind of meeting?

If you live in an HOA or Condominium, or are on the board in one, you are probably getting notices left and right about meetings.

What's the difference between a board meeting and a town meeting, or an annual meeting and a special meeting? Confused? Here's some clarification.

ANNUAL MEETINGS

Annual meetings—or annual membership meetings—are usually required by your governing documents, which specify when they’re to be conducted and how and when members are to be notified about the meeting. This is the main meeting of the year when members receive the new budget, elect a board, hear committee reports and discuss items of common interest. Click here for our HOA/Condo annual review meeting checklist or view below.

SPECIAL MEETINGS

Special meetings are limited to a particular topic. When the Board calls a special meeting (which they can do at any time), they must notify all members in advance. The notice will specify the topic so interested members can attend. Special meetings give the board an opportunity to explore sensitive or controversial matters—perhaps an assessment increase. Members do not participate in the meeting, unless asked directly by a board member, but they have a right to listen to the board discussion.

TOWN MEETINGS

Town meetings are informal gatherings intended to promote two-way communication; full member participation is essential to success. The board may want to present a controversial issue or explore an important question like amending the bylaws. The board may want to get a sense of members’ priorities, garner support for a large project or clarify a misunderstood decision.

BOARD MEETINGS

Most of the business of the association is conducted at regular board meetings. Board members set policy, oversee the manager’s work, review operations, resolve disputes, talk to residents and plan for the future. Often the health and harmony of an entire community is directly linked to how constructive these meetings are.

EXECUTIVE SESSION

The governing documents require the association to notify you in advance of all meetings, and you’re welcome—in fact, encouraged—to attend and listen. The only time you can’t listen is when the board goes into executive session. Topics that the board can discuss in executive session are limited by law to a narrow range of sensitive topics. Executive sessions keep only the discussion private; no votes can be taken. The board must adjourn the executive session and resume the open session before voting on the issue. In this way, members may hear the outcome, but not the private details.

PARTIES

Occasionally the association notifies all residents of a meeting at which absolutely no business is to be conducted. Generally these meetings include food and music, and they tend to be the best attended meetings the association has. Oh, wait! That’s a party, not a meeting. Well, it depends on your definition of meeting.

Take a look at our annual meeting checklist below.

Tips for Saving on Homeowners and Renters Insurance

How to save on your homeowners and renters insurance policy.

Note to renters: Renters, if you don't have insurance you should. Paying $3-5 a month (less than $100 a year), will save you and your bank account a world of pain if disaster strikes on your rental. For example, if the roof leaks or if there's a bug infestation and you need to leave your apartment for a few days, your rental insurance policy will often cover hotel expenses while the landlord remedies the problem.

Whether you own or rent your home, insurance is essential to protect your property and household goods. Comparison shopping for the best rates will certainly save you some money, but you also can save by following these tips:

- Choose a higher deductible—increasing your deductible by just a few hundred dollars can make a big difference in your insurance premium.

- Ask your insurance agent about discounts. Dead bolts, smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, security systems, storm shutters and fire-retardant roofing material are just some of the home safety features that can often lower your rate. You also may be able to get a lower premium if you are a long-term customer or if you bundle other coverage, such as auto insurance, with your provider. Some companies also offer senior discounts for customers who are older than 55 years.

- Don’t include the value of the land when you are deciding how much coverage to buy. If you insure your house, but not the land under it (e.g. in a condominium) , you can avoid paying more than you should. Even after a disaster, the land will still be there.

- If you’re a renter, don’t assume your landlord carries insurance on your personal belongings. They likely don’t provide renters insurance. Purchase a separate renters’ policy to be sure your property—like furniture, electronics, clothing and other personal items—is covered.

Don’t wait until you have a loss to find out whether you have the right type and amount of insurance. For example, many policies require you to pay extra for coverage for high-ticket items like computers, cameras, jewelry, art, antiques, musical instruments, and stamp and coin collections.

Furthermore, not all coverage will replace fully what is insured. An “actual-cash-value” policy will save you money on premiums, but it only pays what your property is worth at the time of loss (your cost minus depreciation for age and wear). “Replacement” coverage gives you the money to rebuild your home and replace its contents.

Furthermore, not all coverage will replace fully what is insured. An “actual-cash-value” policy will save you money on premiums, but it only pays what your property is worth at the time of loss (your cost minus depreciation for age and wear). “Replacement” coverage gives you the money to rebuild your home and replace its contents.

Finally, a standard homeowners’ policy does not cover flood and earthquake damage. The cost of a separate earthquake policy depends on the likelihood of earthquakes in your area. Homeowners who live in flood-prone areas should take advantage of the National Flood Insurance Program.

Applying the Oregon Planned Community Act

The Oregon Planned Community Act (ORS Chapter 94) was adopted in the early 1980s. The Act applies to any subdivision where the owners have collective obligations. Collective obligations include maintaining common property or paying assessments that are used for association operations. A community may be subject to ORS Chapter 94 even if created prior to the adoption of the Act and even if the governing documents make no mention of the statute.

The applicability of the Act depends on the year the community was created, the number of lots, and the total amount of annual assessments. The number of lots and the total amount of annual assessments determine the "class" of the planned community. Class 1 planned communities contain at least 13 lots with at least $10,000 in total annual assessments. Communities with 5-12 lots and at least $1,000 in total annual assessments are Class 2 planned communities. All other subdivisions with collective obligations are considered Class 3 planned communities.

For Class 1 and Class 2 planned communities created prior to 2002, certain provisions of the Act apply to the extend the statute is consistent with the governing documents. Here is a quick way to determine which portions of ORS Chapter 94 apply to your community (if created before 2002): https://calaw.attorney/ors94applicability

Bruce Lepore - Lewis & Clark Law Scholarship Recipient

Congratulations to our colleague Bruce Lepore for earning the coveted Larry Kressel Memorial Scholarship! The scholarship is a memorial scholarship dedicated to Larry Kressel, former professor at Lewis & Clark Law School, who was one of Oregon’s best land use planning attorneys. Eileen “Ikie” Kressel who established the scholarship in honor of her husband Larry, wanted to recognize an outstanding student in the area of land use law. We are thrilled that not only is Bruce at the top of his class but also that he was chosen as the recipient of this award.

Bruce is currently in his final year of law school at Lewis & Clark Law School. When Bruce graduates in Summer 2018 (with top marks), he will be joining the firm full-time as a Partner.

Keep up the good work Bruce!

- Congrats from the CALAW Team

Indemnity and Hold Harmless Provisions in Association Contracts

Condominium and homeowner associations frequently enter into contracts with third-parties. Examples include landscaping contracts, management contracts, and construction contracts. In order to protect the interests of the association, many community association attorneys include indemnity provisions in the contract. Here’s a common example of an indemnity provision:

Contractor will indemnify, defend, and hold harmless the Association from and against any and all claims of every kind, whether known or unknown, resulting from or arising out of Contractor’s work under this agreement.

In this example, the contractor is the “indemnitor” and the association is the “indemnitee”. What is the effect of this language? Let’s assume the Contractor is a landscaper hired to take care of the common areas of the community. One day the Contractor is trimming tree branches. Standard practice requires one worker to operate the saw, and another worker to control the direction of the falling branch. The contractor is short staffed, and there is no second worker to control the direction of the falling branch. A cut branch falls on a unit owner’s exterior deck and damages patio furniture and a BBQ grill. The unit owner then sues the association and wins a judgment for the damaged property.

If the agreement between the association and the contractor contains indemnity language, then the contractor is required to hire and pay for an attorney to defend the association, as well as pay the judgment against the association.

Indemnity provisions don’t transfer liability—the contractor caused the damage and remains legally liable. Instead, these provisions shift the financial obligation related to the claim from the indemnitee to the indemnitor.

Typical indemnity provisions fall into one of three categories: limited, intermediate, and broad. In Oregon, broad indemnity provisions are prohibited by law. I’ll explain each type of indemnity category.

1. Limited indemnity

The limited form indemnity obligates the indemnitor to save and hold harmless the indemnitee only for the indemnitor's own negligence. Let’s go back to our landscape contractor example. In that example, the property damage was caused entirely by the negligence of the contractor. The association did not cause or contribute to the damage. Here, the contractor must indemnify the association.

2. Intermediate

The intermediate form of indemnity obliges the indemnitor to hold harmless the indemnitee for all liability except that which arises out of the indemnitee's sole negligence. Back to the landscape contractor example. Let’s now assume that the tree branch fell much quicker and forcefully than normal because the tree is decaying. Also assume that the association has known that the tree is decaying and decided not to address the issue. In this case, both the contractor and the association are negligent and the contractor is required to indemnify the association.

The contractor would not be required to indemnify the association if the cause of the damage resulted entirely from the association’s negligence. Let’s now assume that the contractor has not touched the tree and the tree branch fell because of rot and decay. In this case, the damage resulted entirely from the association’s negligence. The contractor has no obligation to indemnify the association.

3. Broad

The broad form of indemnity requires the indemnitor to save and hold harmless the indemnitee from all liabilities arising from the project, regardless of which party's negligence introduces the liability. Under this category, the contractor is required to indemnify the association even if the association contributed to the damage or was entirely responsible for causing the damage. This form of indemnity is prohibited under ORS 30.140:

(1) Except to the extent provided under subsection (2) of this section, any provision in a construction agreement that requires a person or that person’s surety or insurer to indemnify another against liability for damage arising out of death or bodily injury to persons or damage to property caused in whole or in part by the negligence of the indemnitee is void.

(2) This section does not affect any provision in a construction agreement that requires a person or that person’s surety or insurer to indemnify another against liability for damage arising out of death or bodily injury to persons or damage to property to the extent that the death or bodily injury to persons or damage to property arises out of the fault of the indemnitor, or the fault of the indemnitor’s agents, representatives or subcontractors.

When entering into a third-party contract for any services related to construction, the association should always have a qualified attorney review the agreement. As part of that review, the attorney should make sure that the indemnity provisions do not fall under the “broad indemnity” category.

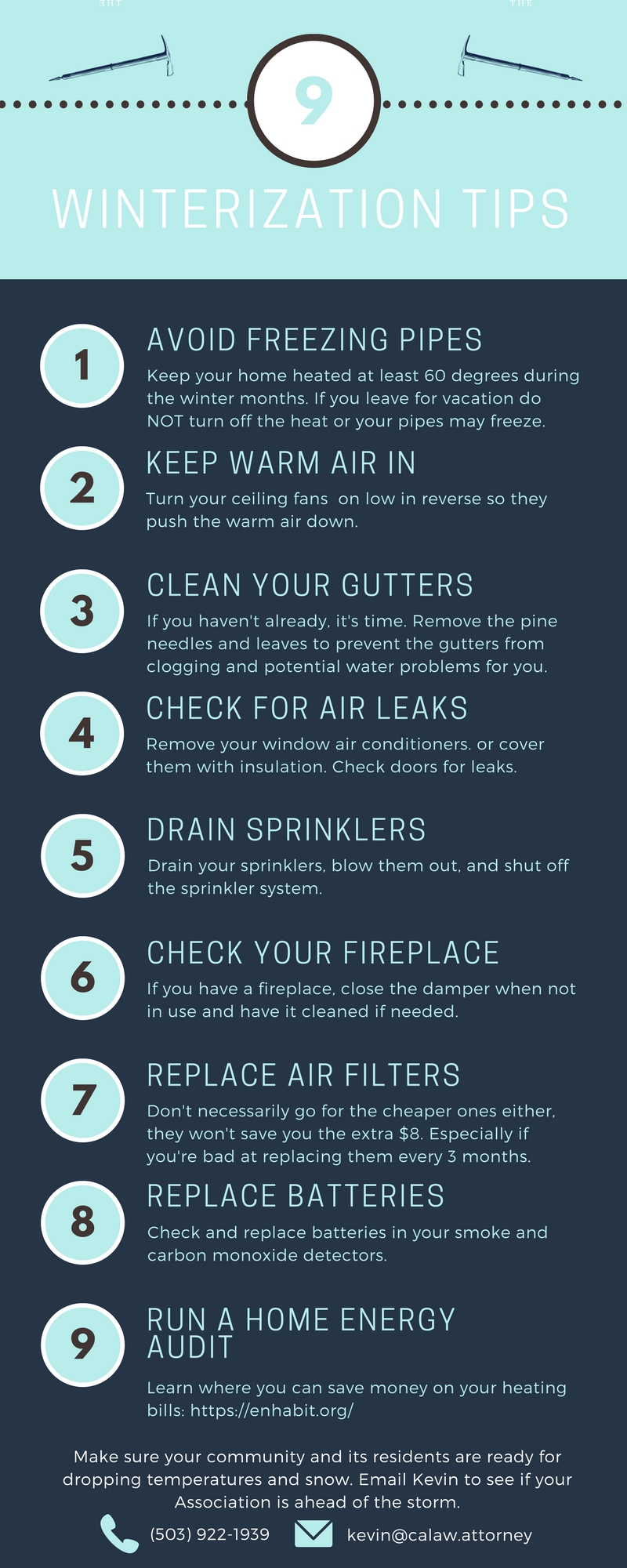

Are You Ready for Cold Weather?

Fall is the time to prepare for winter—cold and wet conditions not only make you miserable, but they can damage your home. Now is the time to start if you haven't already. Better late than never. Some winterizing can wait, some can’t. Make a list of what needs to be done, and tackle the time-sensitive tasks first. Here’s a few tips to help you get a jump on winter and stay cozy when the temperatures drop.

Adverse Possession

The doctrine of adverse possession can be found in the Code of Hammurabi, written around 2000 B.C.E. The doctrine was also observed by the ancient Romans. American property law (inherited from the British) recognizes the idea that one property owner can take title to land belonging to someone else. Adverse possession claims frequently arise in community associations. For example, suppose an owner’s lot is adjacent to common property, and over the years the owner gradually builds a flower bed, installs a play structure, and mows the grass several times throughout the year. If this continues for 10 years, the owner may claim adverse possession and take title to part of the common property.

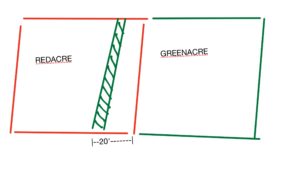

Suppose there are two adjacent parcels. We’ll call them “Redacre” and “Greenacre”:

Now, suppose the owner of Greenacre decides to built a fence. But when the fence is constructed, it’s on Redacre’s property:

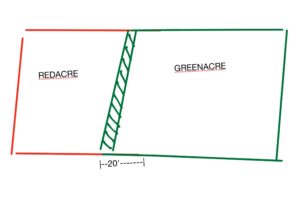

After a period of 10 years (and assuming the requirements of adverse possession are met), the owner of Greenacre may take title and ownership of the 20’ strip of land:

In order to establish a claim for adverse possession, the claimant must prove that the use is:

- Open and Notorious

- Exclusive

- Hostile

- Continuous

Open and notorious means that the claimant has left no doubt in the mind of the true owner of the potential adverse possession claim. The type of use or occupation must be consistent with the nature of the land. For example, planting trees on property that already has shrubs, bushes, and trees, is not open or notorious. That wouldn’t be an obvious adverse use. Limited use of property isn’t open or notorious, either. Occassional hiking or hunting on someone else's land doesn’t meet the requirement.

The next element is exclusive use. This doesn’t mean the claimant must use or occupy the property on a daily basis. Exclusive possession only requires occupancy that is characteristic of exclusive ownership. Building a fence is almost always considered exclusive use. But cattle occasionally breaking through a neighbor’s fence and grazing is not considered exclusive use. Cattle frequently wander onto adjacent parcels of land.

Things get tricky when it comes to proving the “hostile” requirement. Whether possession or use is hostile depends on the mindset of the claimant. In most cases, a mistaken belief of land ownership constitutes hostile. Suppose I purchase property and wrongly assume that my boundary line is 50 feet beyond the true boundary line. I then build a shed within the 50’, all the while believing it’s my land. That mistaken belief satisfies the hostile requirement.

Lastly, my adverse use or possession must be continuous. In most states, continuous means a period of at least 10 years. However, claimants may take advantage of “tacking”. Let’s say John builds a fence on the neighbors property and has satisfied all of the other requirements of adverse possession. After 3 years, John sells to Jill, who after only 1 year, sells to Jack. Using “tacking”, Jack may use the previous 4 years of ownership by John and Jill to meet the 10 year requirement.

Getting title through adverse possession isn’t as simple as declaring you’ve met all the requirements. Title is granted by a court through lawsuit to “quiet title.” In other words, the claimant must prove to a judge that each and every element of adverse possession has been satisfied.

For property owners who think they may be subject to an adverse possession claim, there are couple of options—all of which must be exercised before the 10 year period. First, the true owner may file a claim for trespass. If I notice my neighbor building a fence on my property, they are technically trespassers. Similarly, the true owner may preemptively file a suit to quiet title.

The Meaning of Quorum

Most community association bylaws state a specific quorum requirement for owner or membership meetings. The purpose of a quorum is to avoid binding owners to decisions made by an unrepresentatively small number of individuals. Simply put, quorum is the minimum number of members or owners required to conduct business at a meeting. That minimum number may be a percentage of owners or a specific, fixed number of owners. If at the start of an owner meeting it appears the quorum requirement has not been met, the meeting cannot continue. The only action that may be taken is to set the time and place for another meeting. Any substantive action taken in the absence of a quorum is deemed invalid.

Some governing documents may not provide for a quorum requirement. In that case, there are statutory defaults. In Oregon, if the governing documents are silent then the quorum requirement is 20% of the owners (ORS 94.655). Washington has a slightly larger default quorum requirement:

Unless the governing documents specify a different percentage, a quorum is present throughout any meeting of the association if the owners to which thirty-four percent of the votes of the association are allocated are present in person or by proxy at the beginning of the meeting.(RCW 64.38.040)

Keep in mind that quorum can be achieved by owners attending a meeting in person or by proxy. It’s conceivable that quorum could be achieved by only a few owners attending a meeting in person, but each of those owners having multiple proxies from other owners.

If your homeowner or condominium association has difficulty meeting its quorum requirement, here are a few ideas to consider to increase membership attendance:

- Consider changing the location to a more convenient or comfortable place;

- Plan ahead and choose a meeting date that doesn’t conflict with vacation periods or holidays;

- Send notice of the meeting via mail, email, and any other means which owners are likely to receive;

- Consider serving food or refreshments;

- Give away door prizes.

Robert's Rules for Condominiums and HOAs

Most community associations use parliamentary procedure to govern board and owner meetings. In the United States, the most popular form of parliamentary procedure is Robert’s Rules of Order. Complicated? Surely. But if you understand a few basics, you can learn how to run a civil and efficient meeting. Here’s the key to Robert’s Rules: 1) Motion 2) Second 3) Debate 4) Vote. The entire meeting should follow those steps.

First, a member of the assembly makes a motion. This is how business is brought before the group. Standing up and complaining, or voicing a concern, is not a motion and is “out of order.” Instead of standing up to complain about the state of disrepair of the clubhouse, I can make a motion. For example: “I move that we spend $2000 to repair the clubhouse.”

Next, another member of the assembly must second the motion. This simply ensures that at least one other member wishes to debate the motion. If a second is not received, the motion dies and a new motion may be entertained.

Now is the time to debate the motion. Members of the assembly take turns explaining why the assembly should vote for or against the motion.

Once the debate is closed, the assembly votes on the motion. Then the chair announces the outcome of the vote and a new motion may come before the assembly. The process repeats itself until a motion to adjourn the meeting is made.

To be sure, there are dozens of nuances and technical details. For example, during debate of a motion the maker of the motion speaks first, you alternate between those for the motion and those against the motion, those who haven’t spoken get precedence over those that have, etc., etc. Don’t get hung up on the technical aspects—-just remember: Motion, Second, Debate, Vote. That’s 99% of knowing Robert’s Rules.

Click here for a simple chart of parliamentarian motions: Motions Chart